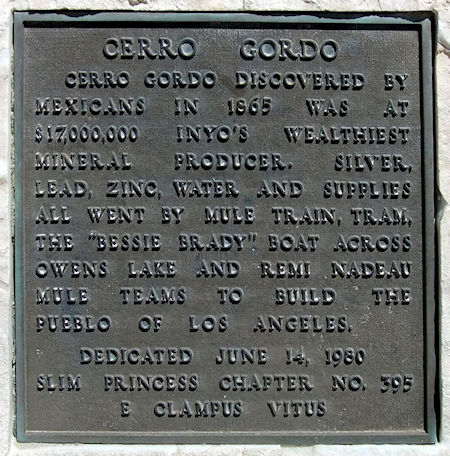

Historic marker placed by the Slim Princess Chapter No. 395 of E Clampus Vitus on June 14, 1980, at the bottom of the old Yellow Grade Road, aka Cerro Gordo Road, where it veers off from today's Highway 136 on the east side of Owens (Dry) Lake. Marker reads:

CERRO GORDO

Cerro Gordo discovered by Mexicans in 1865 was at $17,000,000 Inyo's wealthiest mineral producer. Silver, lead, zinc, water and supplies all went by mule train, tram, the "Bessie Brady" boat across Owens Lake and Remi Nadeau mule teams to build the Pueblo of Los Angeles.

Pablo Flores, a prospector who possibly hailed from Nicaragua and studied mineralogy at the Colegio de Minirio (established 1793) in Mexico City, had been scouring the hills of California and Nevada for precious metals when, in 1865, he discovered silver and lead (which occurred together) on Buena Vista Peak in the Inyo Mountains, located between the Sierra Nevada on the west and Death Valley on the east.

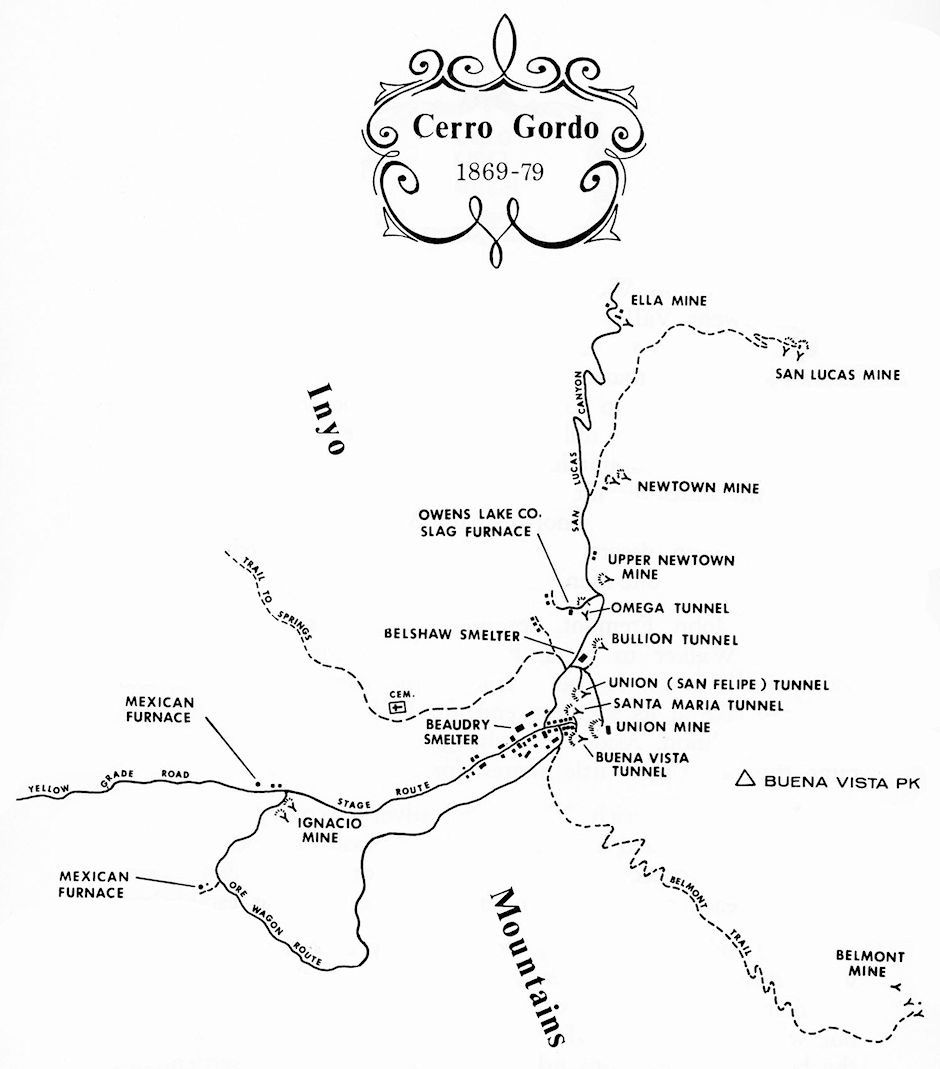

Buena Vista Peak was renamed Sierra Gordo and then Cerro Gordo ("Fat Hill"). The peak sits eight miles east and 5,000 feet above Owens Lake. It became part of the Lone Pine Mining District, formed April 5, 1866, in response to the discovery. When federal mining laws were implemented in 1872, the area was reorganized into the separate Cerro Gordo Mining District.

By 1867, tales of the silver at Cerro Gordo had spread, bringing in flocks of new prospectors. For the first few years, Mexicans worked the surface exposures and smelted the ores in crude smelters or "vasos". When news of the discovery reached the Comstock Lode, the rush to Cerro Gordo was on.

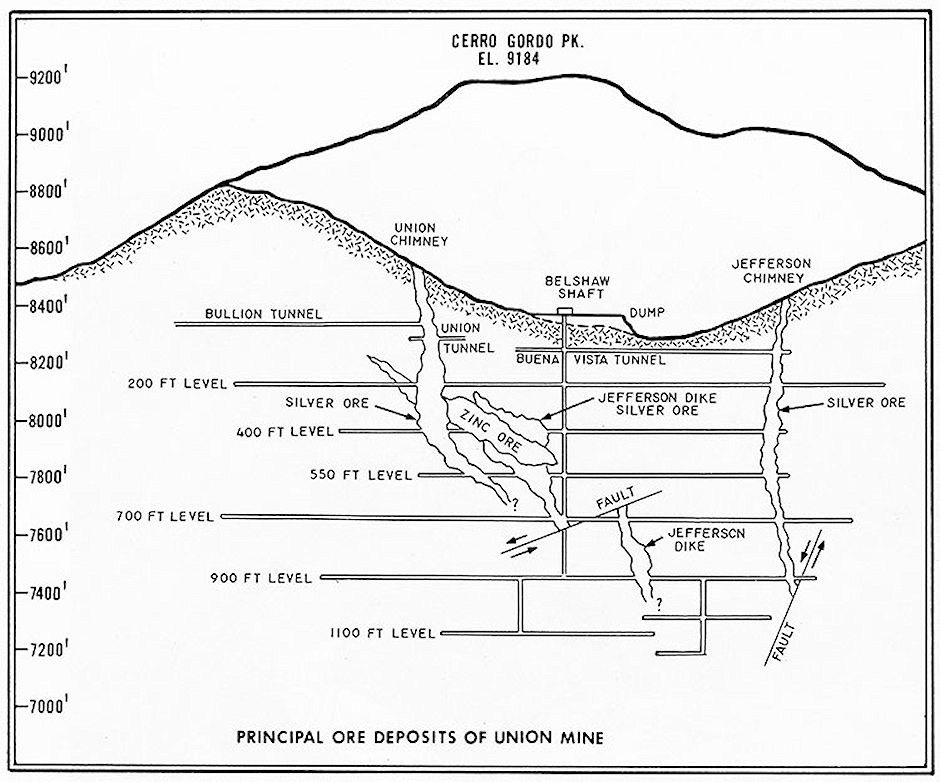

For the first few years after the discovery in 1865, the exposed ore bodies at Cerro Gordo were worked in pits and trenches. By 1870, the Union Mine's Union Chimney had become the most important working and was being developed by a vertical shaft and by the Union Tunnel (65 level) which was driven eastward 400 feet to encounter the chimney 175 feet below its outcrop. Similarly, the rich Jefferson Chimney was mined vertically to the level of the Buena Vista Tunnel.

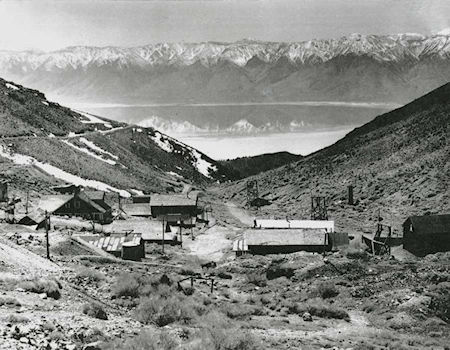

Cerro Gordo when there was water in Owens Lake (Friends of Cerro Gordo Collection)

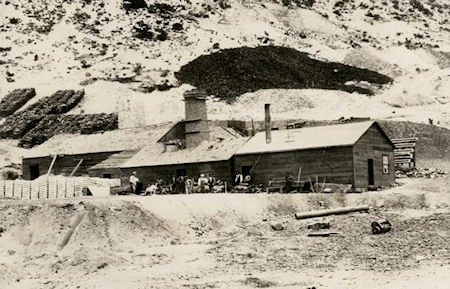

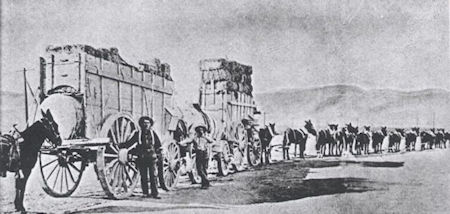

Mules and freight wagons can be seen outside of the original mule barn. Remi Nadeau's teams and drivers were the primary freighters of the silver and trade that went back and forth from Cerro Gordo and Los Angeles (Friends of Cerro Gordo Collection)

An estimated $17 million worth of silver and lead ore — $400 million in 2013 dollars — poured out of the Cerro Gordo mines. From the late 1860s to the late 1870s, it passed along a 200-plus-mile journey to the emerging pueblo of Los Angeles. Teamsters driving 14 mules, on average, stopped at a dozen different watering holes along the way.

Teamsters had to be on the lookout for highwaymen like Tiburcio Vasquez and his lieutenant Cleovaro Chavez, who demanded what might politely be called tolls. With dozens of mule teams plying the route in both directions — to Los Angeles with ore; back to Cerro Gordo with fodder, liquor and sundries — teamsters sometimes managed to warn each other of bandit activity when their paths crossed. In those instances, it's said they would stash their ore along the road for later retrieval.

Victor Beaudry

That got the attention of a Quebec-born sutler at Fort Independence, Victor Beaudry, who opened a general store to serve the miners. Smelting ore in crude furnaces and using "vasos" (vessels) to refine it into a portable silver and lead mixture, the miners traded it for provisions at Beaudry's store.

The brother of Los Angeles real estate tycoon and later L.A. mayor (1874-76) Prudent Beaudry, Victor Beaudry extended enough credit to enough miners that he was soon able to foreclose on their claims and gobble up most of the Cerro Gordo mines, including a half-interest in the largest, the Union, perched above the camp.

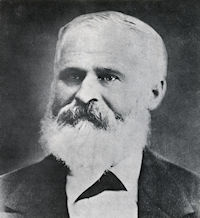

Mortimer W. Belshaw

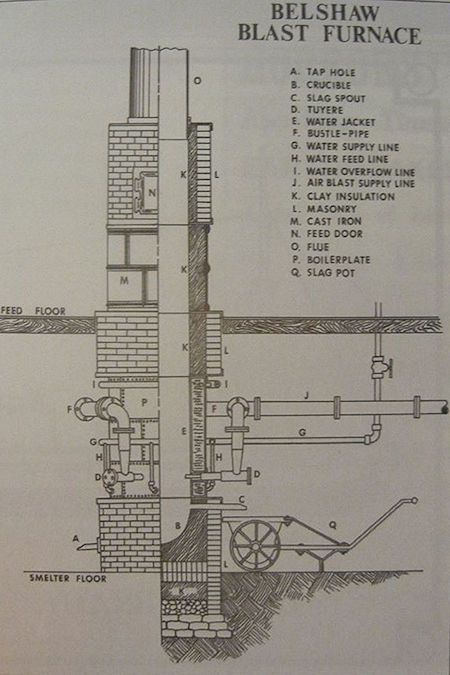

In April 1868, mining engineer Mortimer Belshaw arrived from San Francisco. He immediately recognized the richness of the ores and the need for a smelter to efficiently process the ore. Seeing opportunity, he bought an interest in the Union Mine, the richest mine in the district, in exchange for an interest in the first smelter he was to build at Cerro Gordo.

Belshaw and his partner, Abner B. Elder, took some smelted ore via San Pedro to San Francisco, where they organized the Union Mining Co. with a third partner and financial backer, Egbert Judson, president of the California Paper Co.

Rare photo of the Belshaw smelter. Note the stack of bullion bars (front left of the smelter). It is difficult to believe this shabby looking smelter was capable of producing silver bullion at a faster rate than had ever been recorded in the United states. The building may have given the appearance of being in disrepair, but Belshaw's blast furnaces were at the cutting edge of silver smelting, and could produce 5.25 tones of bullion in 24 hours. The large dark area directly above the furnace stack is not smoke, but most likely, the huge surface pit (outcrooppng) of the Union Chimney, an excptionally rich deposit of galena (silver/lead) that ran 15-70 feet wide and 760 feet deep.

Belshaw Smelter Furnace (Friends of Cerro Gordo Collection)

Belshaw and Elder returned to Cerro Gordo, built an eight-mile toll road up the mountainside from Owens Lake — the Yellow Grade Road (named for the yellowish shale) — and fired up a new, steam-powered smelter in September 1868 near the mountaintop above the camp, the Belshaw-Judson works based on his own methods for fluxing and smelting the Cerro Gordo ores.

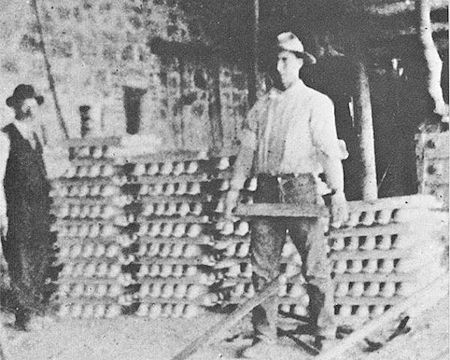

Elder kept the furnace going 24/7 and produced 120 silver-and-lead ingots daily, each measuring 18 inches long and weighing about 85 pounds. Not satisfied with its early output, Belshaw invented and installed the Belshaw water jacket which equalized the heat in the furnace and resulted in output of 5 tons of bullion (worth $3,500) per day.

Remi Nadeau about 1880

In December 1868, Belshaw and Beaudry hired another French Canadian, the famous freighter Remi Nadeau (1819-87), to haul the ore to Los Angeles. Thirty-two teams carted $50,000 worth of silver and lead — only half of the maximum output — down the Yellow Grade Road every day to start a three-week trek to Los Angeles where the silver and lead were separated at a proper refinery.

In 1870, the Union Mine was the most prolific of the Cerro Gordo Mines and was developed by a vertical shaft on the Union Chimney and by the Union Tunnel which struck the ore body 175 feet vertically below the discovery pit.

Remi Nadeau 22 mule team hauling hay to early mining regions of the Mojave Desert. Rigs piled this high were apt to be blown over in windstorms. (American Potash & Chemical Company)

In 1870, Victor Beaudry built the second smelter at Cerro Gordo, a somewhat less efficient smelter on the west side of the camp. A chimney from Beaudry's smelter still stands in 2020; Belshaw's doesn't. Rather than compete with each other, Belshaw and Beaudry joined forces and by 1870 were the most powerful men in Cerro Gordo. Production increased to an average of seven tons a day and topped out at nine. The ore literally couldn't be hauled down the mountain fast enough.

In 1870, Beaudry started piping 1,300 gallons of water per day from the Inyo mountain springs to storage tanks at the camp — more information here. Also imported was borax from Death Valley, for use as a flux in the furnaces.

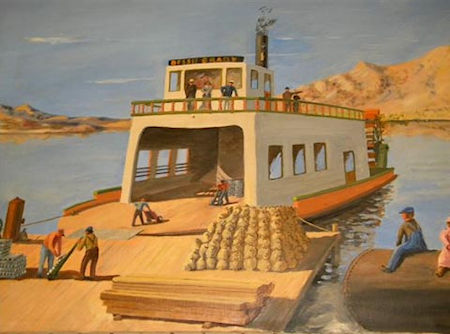

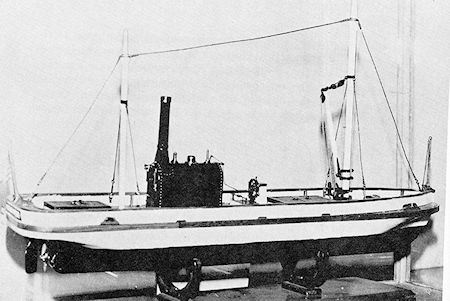

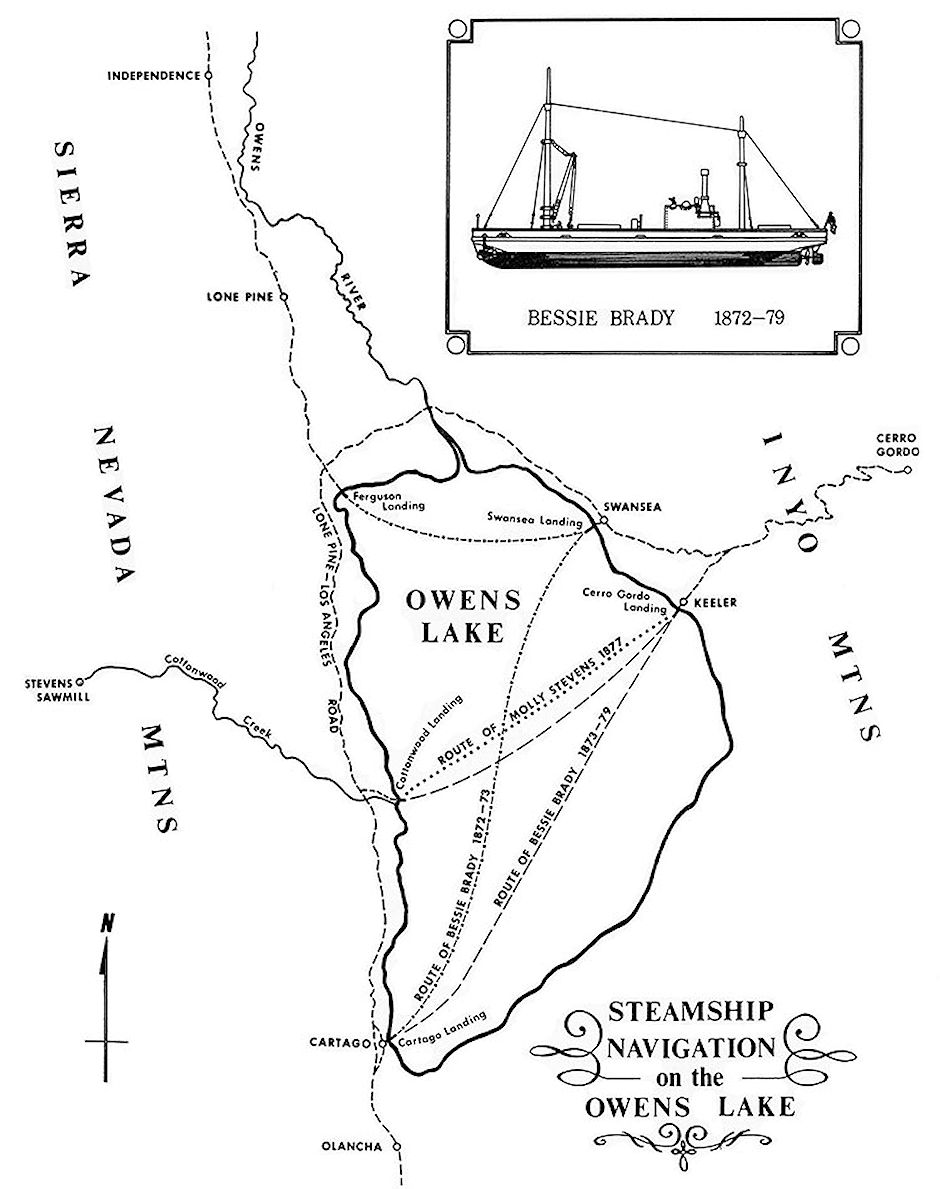

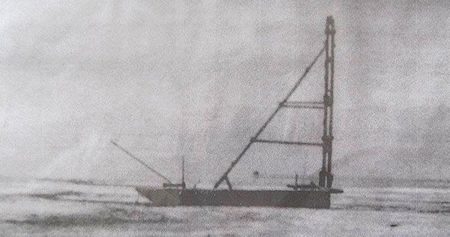

Nadeau's shipping contract expired in December 1871 and it went to James Brady who, in June 1872, built and launched an 85-foot steamer, the Bessie Brady, named for his daughter, to ferry ore from Swansea, the town he established on the east side of Owens Lake, to Cartago on the west side. This shaved a few dollars and a couple of days off of the transport.

Torrential rains and other complications hampered freighting, and Brady couldn't properly perform on his contract. The ingots piled up. Plus, at this time, Brady and Belshaw were at odds over conflicting mining rights on the mountain (bound to happen when one man owns a mining claim and another purports to own the lode that the first man intends to mine). Brady won the argument in court but lost the shipping contract.

For more on the Bessie Brady read this article: The Saga of the Bessie Brady

Painting of the Bessie Brady by William McKeever on display at the Eastern California Museum in Independence, CA

Model of Bessie Brady Steamer

Steam ship navigation routes on Owens Lake

For the first few years the teams of huge freight wagons delivered so much silver bullion from Cerro Gordo that the Los Angeles News, in February, 1872 stated,"To this city, Cerro Gordo trade is invaluable. What Los Angeles now is, is mainly due to it. It is the silver cord that binds our present existence. Should it be unfortunately severed, we would inevitably collapse."

The property ultimately turned it into the largest producer of silver and lead in California, yielding ores that assayed at least as high as $300 per ton.

Two chunks of raw, silver-bearing galena (lead sulfide) from inside the mines at Cerro Gordo, and a small ingot that was smelted from it. Sold as a souvenir today, the little 2.75x0.5" ingot is similar in composition to the 18-inch-long, 85-pound ingots that were shipped from Cerro Gordo to Los Angeles during the mines' heyday

Robert Desmarais, the caretaker/historian at Cerro Gordo and a retired schoolteacher, displays a pig of silver and lead that was smelted by the early Mexican miners prior to the introduction of steam power and the construction of a modern furnace

Extracting silver: Silver-bearing galena (lead sulfide, upper left) is smelted into a cone (bottom left) which is then super-heated to 900 degrees in a cupel (a porous cup made of bone ash, center), at which point the lead oxides and the silver separates out to form a "button" (right)

A boulder-sized mass of sulfur crystals from inside the Cerro Gordo silver and lead mines

Ore cart, used to haul galena out of the Cerro Gordo mines. On display in the Cerro Gordo mining camp, where it's used as a bin for slag. Behind it, a volunteer is helping to restore the Crapo house

Workers display the 18-inch-long, 85-pound silver-lead ingots that were shipped by wagon from the Cerro Gordo mines to Los Angeles. One days run at the Cerro Gordo F. M. Smelter.

Robert Desmarais, the caretaker/historian at Cerro Gordo and a retired schoolteacher, displays a pig of silver and lead that was smelted by the early Mexican miners prior to the introduction of steam power and the construction of a modern furnace

Extracting silver: A crucible (top left) is used to smelt the silver-bearing galena (lead sulfide, bottom left corner) into a form that can be super-heated to 900 degrees in a cupel (a porous cup made of bone ash, bottom), at which point the lead oxides and the silver separates out to form a "button" (at right)

Slag from Cerro Gordo - the waste material that's left over after the raw galena (lead and silver ore) is smelted in a blast furnace

Slag from Cerro Gordo - the waste material that's left over after the raw galena (lead and silver ore) is smelted in a blast furnace

Ore cart, used to haul galena out of the Cerro Gordo mines. On display in the Cerro Gordo mining camp, where it's used as a bin for slag. Behind it at center is the American Hotel; at left is the Crapo house

Between 1865 and 1877, various tunnels were driven eastward on the west flank of the peak to work specific shallow ore bodies. The more significant of these were the Buena Vista and the Santa Maria tunnels.

The Buena Vista Tunnel (at the 68' level) was driven eastward almost 350 feet to intersect the Buena Vista Fault. The tunnel continued 400-500 feet south along the fault and east to work the Jefferson Chimney on the south end of the mine area (this tunnel was opened up and extended as the 86 level in the later Belshaw Shaft).

The Santa Maria Tunnel (at the 90' level) extended 400 feet southeast to access the Santa Maria quartz vein.

North of the Union Chimney, the Bullion Tunnel (at the 42' level) was driven 300 feet east to exploit the Bullion Vein surface exposure and approximately 600 feet of north and south drifts were driven along the vein.

The Omega Tunnel (at the 200' level) was driven about 700 feet southeast to the ore bodies along the Omega Fault.

Similarly, the Zero Tunnel (at the 0' level) extended 200 feet east to intersect the Zero Vein which was drifted northward for approximately 100 feet.

Over the years, numerous exploratory drifts have been driven from these tunnels adding several miles to their original courses.

By 1872, Cerro Gordo was a well-established camp with eleven active mines in the district. Regular shipments of lead-silver bullion were being shipped to San Francisco by way of Los Angeles and San Pedro. This early trade with the settlement of Los Angeles was largely responsible for its survival and growth.

In 1873, the Owens Lake Silver Mining and Smelting Company, owners of the San Filipe Mine interfered with Belshaw's plans to take control of all of Cerro Gordo by disputing Belshaw's claim to the Union Lode. The San Filipe Mine exploited a silver quartz vein near the Union shaft.

Originally surface works, they purchased a local tunnel (San Filipe Tunnel) and began driving it towards the vein until Belshaw noticed galena on their waste dumps. Belshaw alleged they were mining his Union Chimney lode and in response made claim to the Santa Maria and San Felipe claims.

Meanwhile, Beaudry acquired the mortgage on the San Filipe Tunnel and foreclosed to shut down their operations. These actions led to bitter and lengthy litigation when the Owens Lake Company countered with a claim to the Union Mine.

The courts finally ruled in favor of the Owens Lake Company, giving them rights to the Union Mine. Belshaw appealed the decision to the State Supreme Court and in 1876, the litigation was concluded with the San Filipe owners settling for a small interest in the Union Mine. The two opposing companies combined the properties into the Union Consolidated Company which included the San Filipe and Santa Maria veins, the Union Chimney, and the Cerro Gordo Fault and its associated ore bodies.

Nadeau agreed in June 1873 to resume shipping, on condition that the two "bullion kings," Belshaw and Beaudry, would make him a full partner in the new Cerro Gordo Freighting Co. and spend $150,000 to build stations a day's ride apart.

In 1874, the Southern Pacific Railroad pushed north as far as San Fernando, so after clattering through Beale's Cut on its southern journey, the ore traveled by train the rest of the way.

Belshaw refurbished his furnaces which were now producing 400 ingots daily, double the 1871 rate.

As many as 100 Nadeau teamsters driving 80 teams consisting of 14 mules and three high-sided wagons carried $700,000 worth of ore annually to Los Angeles and spent half that much, about $1,000 daily, on local farmers' entire surplus feed crops — 2,500 tons of barley and 3,000 tons of hay, or roughly 27 percent and 40 percent, respectively, of Los Angeles County's entire yield.

Cerro Gordo's population at this time tipped the scales at 4,500 — a mix of Anglo, Indian, Hispanic and Chinese workers, most living in bunkhouses and earning a top rate of $4 per day. The mining camp sported general stores, saloons, restaurants, at least two hotels (including the lavishly appointed American Hotel built in 1871 by Mr. and Mrs. John Simpson), two competing dance hall-brothels (one burned down mysteriously one night in March 1880, along with eight other buildings), doctors', lawyers' and assay offices and blacksmiths — but no church, school or jail. Payday was followed by carousing at the saloons and brothels and often ended in gunfire; men sandbagged their bunks to insulate themselves against stray bullets.

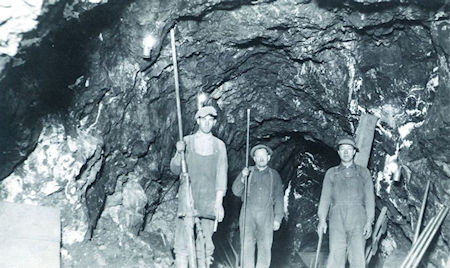

Inside the mines (L. D. Gordon Collection)

Cerro Gordo's peak production occurred in 1874 with its smelters producing eighteen tons a day of lead-silver bullion. During this time, the output of a single smelter at Cerro Gordo amounted to 300 silver lead "base-bullion" bars each weighing 87 pounds and valued at $335 each. The freight wagons could not keep up with output and the bullion bars stacked up like cordwood and were frequently used to build temporary buildings and shelters.

The lack of water was an early problem. Water was originally imported by pack train or acquired from snowmelt in the winter. In 1874, a pipeline was brought in from the Cerro Gordo Spring, 3 miles to the north. Steam pumps lifted water 1,860 vertical feet to storage tanks at the summit, from where it flowed by gravity. This cut the cost of water in half but was plagued by freezing in winter. This water system remained in operation until the 1930s. More details here.

Major mining activity slowed after 1876, when Belshaw shut down his furnace. A fire destroyed the Union Mine hoist works in August 1877; they were repaired, but now the mine was in debt. Wages were cut to $3 a day and half of the miners left.

In 1877, when the ore quality declined and the principal workings had been consolidated into the Cerro Gordo Mines, a new vertical shaft, the Belshaw Shaft, was sunk to a 900-foot depth in an effort to explore for deeper ore bodies to stop the decline in ore coming from the mine and to serve as the main mine entrance.

The main reason for the shaft was to locate the continuation of the Union Chimney which was lost at the 550 level, presumably by faulting. The shaft was sunk vertically to 900 feet with levels at 86, 200, 400, 550, 700, and 900 feet. Extensive workings were extended to the north, east, and south from these levels but the Belshaw shaft failed to find the continuation of the Union Chimney or any other significant high-grade ore bodies.

Upon completion of the shaft, ore could be hoisted to the Union Tunnel level, then trammed to the Belshaw furnace located 450 feet from the tunnel portal.

The Union closed in October 1879 and a month later, Beaudry's furnace was shut. Nadeau hauled out the last 208 ingots and a 420-pound glob of silver on November 21, 1879 and the Belshaw-Judson Furnaces were shut down the following year. Cerro Gordo was nearly deserted when the last load of bullion was shipped in 1879.

Julius M. Keeler arrived in Owens Valley in the winter of 1879-80. As an agent for D. N. Hawley, Keeler represented the Owens Lake Mining and Milling Company. Having purchased the Union Consolidated holdings at Cerro Gordo, Keeler began laying out a town and mill site near the Cerro Gordo landing in March 1880.

Molly Stevens boat used to haul ore across Owens Lake and return with charcoal and supplies

The Owens Lake Mining and Milling Company purchased Colonel Stevens' inactive lumber company as a means of obtaining construction material for the proposed town. The steamer Molly Stevens was included in the purchase.

After the damaged section of the flume was restored, the sawmill was put into operation in October 1880. The Molly Stevens delivered the first consignment of lumber across the lake, and the small community called Hawley began taking shape. The name of the town was later changed to Keeler.

The steamer Molly Stevens did not prove to be as efficient as Julius Keeler had earlier hoped for. The Bessie Brady was pulled off the beach at Ferguson's Landing in the spring of 1882. After being towed to Keeler, her weathered hull was completely reconditioned.

The Molly Stevens was dismantled and the powerful engine from the U.S.S. Pensacola was removed and refitted into the Bessie Brady.

On May 11, 1882, a spontaneous combustion from the oil, paint, and tar turned the Bessie Brady into an inferno. After sparing no expense to restore the steamboat, all that Julius Keeler could do was stand and watch her burn.

The Carson and Colorado Railroad, which reached Keeler in 1883, rekindled interest in Cerro Gordo. The mines were reopened by small mining companies and lessees on a limited basis. While the Union Mine again produced small quantities of ore, exploratory activity produced few new reserves.

By then the early "bullion kings" were gone. Beaudry left in 1876, splitting his time between his home in Montreal and brother Prudence's adopted home of Los Angeles, where Victor died in 1888. Belshaw moved in 1877 to the Northern California town of Antioch where he mined, among other things, and died in 1898.

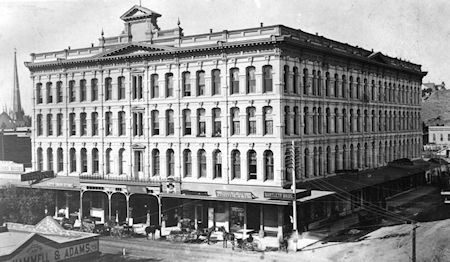

Nadeau Hotel 1886 - Water & Power Associates Collection

For his part, Nadeau invested his money in sugar beets, wine grapes, barley and land in downtown Los Angeles where, in 1886, he built the lavish, four-story Nadeau Hotel, the likes of which the pueblo had never seen. Today it's Times Mirror Square.

But, it was not the end for Cerro Gordo. In 1905, mining activity was revived in the Panamint region, and hope was seen for many of the old productive mines.

In 1905, the Great Western Ore Purchasing and Reduction Company acquired the Union Mine and envisioned building a 100-ton smelter for custom work and also to process ore left on the Cerro Gordo dumps, earlier considered too low grade for the technological methods then in use. By modern methods the ore could be worked profitably.

Cerro Gordo wasn't finished.

They produced a little ore into 1907 at which time the mine was taken over by the Four Metals Mining Company. With the intent of both reopening the mine and working the old smelter slags, the company built a 200-ton smelter near Keeler and built an aerial tramway to connect the two. The company instead went bankrupt.

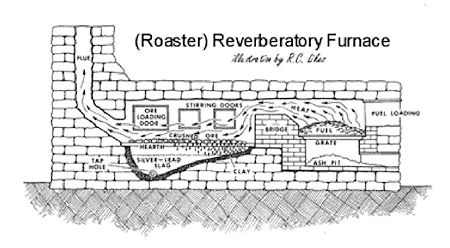

Reverberatory Furnace

The Zinc Era Begins

Then, in 1907, high-grade zinc ore was discovered at the 900- to 1,000-foot level in the Union Mine. A 200-ton reverberatory smelter was constructed at the base of the mountain east of Keeler and a cable tramway was strung above the Yellow Grade Road to carry the ore down in buckets.

Results were mixed until 1911 when Louis D. Gordon and Associates leased the properties. L. D. Gordon and Associates were the first to recognize the value of the zinc carbonate ores.

Union Mine 900 foot level about 1915. That's L. D. Gordon on the left

(L.D. Gordon Collection)

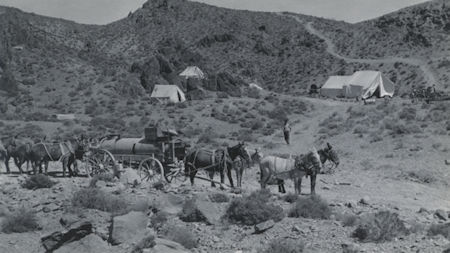

Mule driven wagons carrying water to a construction site for the Leschen tram (L.D. Gordon Collection)

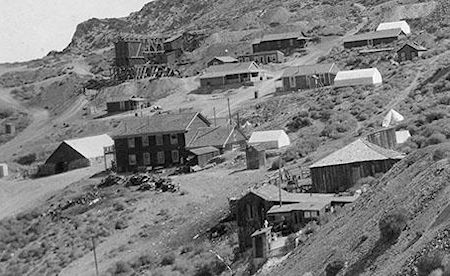

At top just right of center is Lola's dance hall with the girl's cribs below and the roof of the Assay Office just visible. The building below is gone. Slightly below is the Belshaw House with a white tent next to it where the Gordon House was later built in 1909. Center left is the American Hotel with the mule barn to its left. At the bottom right is the Hunter House

In 1911, 160 feet north of the Belshaw Shaft on the 900 level, a winze was sunk to the 1,100 level with drifts on the 1,000 and 1,100 levels. A 250-foot winze was also driven 450 feet south of the main shaft with a drift from the bottom and one at about 1,030 feet. The total underground workings at Cerro Gordo are estimated at approximately 15 miles of tunnels and drifts.

In 1914, Louis D. Gordon and Associates acquired title from the previous owner, the Four Metals Co., and reorganized the properties as the Cerro Gordo Mines Co. The Cerro Gordo Mines became a major source of high-grade zinc carbonate ore between 1911 and 1919.

Tortuous stopes were opened just east of and adjoining the old Union Chimney (China Stope) to exploit the zinc ore. The largest zinc stopes extended upward roughly on bedding incline from the 550 level to the south end of the Bullion Tunnel workings.

The property now consisted of tunnels and shafts and an aerial tramway connecting the mine with the narrow-gauge Southern Pacific Railroad at Keeler. Shipping 1,000 tons of ore daily, Cerro Gordo became the largest producer of zinc carbonates in the entire United States.

Snow blankets Cerro Gordo's Leschen Tram terminal and other buildings in this photograph from the L.D. Gordon Collection taken approximately 1915. House in front is gone. On the right edge is Lola's girls cribs and her dance hall just barely in the picture

Starting around 1915, slag (waste material) from the old dumps was reprocessed. Old tunnels were extended and new tunnels were driven; one, the Estelle, about two miles below camp, started in 1908 and by 1923 had reached the impressive length of 8,100 feet, running straight through half of the upper Inyo mountain range. In all, 37 miles of tunnels snake through the mountain.

Electricity and telephones arrived in 1916. Explorations continued for new silver and lead deposits. With electric power for hoisting, compressors, and to operate a newly constructed 5.6-mile, gravity-powered Leschen and Sons wire-rope aerial tramway which replaced the initial Montgomery tram and moved 20 tons of zinc ore daily to the railroad at Keeler. From there it went to the United States Smelting and Refining Co. in Utah for processing.

From 1911 to 1919, the reopened Union gave up 8,022 tons of lead and 720,000 ounces of silver. During this period, new silver-lead ore bodies were also opened in the Jefferson Dike and Jefferson Chimney.

Cerro Gordo was booming again.

By 1920, about ten men were still employed by the Cerro Gordo mines company and silver-lead ore was being shipped. A few years later, in 1924, silver-lead ore on the old dumps was still being worked. Gross production of the Cerro Gordo camp from its early profitable years up until 1938 was about $17 million.

From 1923 - 1927, Cerro Gordo was operated under lease by a W. W. Waterson. In 1925, a significant new ore body was found by the Estelle Mines Company on the La Despreciada claim west of the old Cerro Gordo Mines. From 1928 - 1929, the Estelle Mining Company leased the Cerro Gordo properties, after which they were leased to the American Smelting and Refining Company which operated them until 1933.

No important discoveries have been made since the La Despreciada ore bodies. During this period the ore mined and shipped amounted to 10,000 tons with a gross value of $305,630. The approximate grade of ore shipped was .053 oz gold, 29 oz silver, 41% lead.

Gordon eventually moved on, and American Smelting of Utah took over the mines. Total yields for 1929 were 3 million pounds of lead, 290,420 ounces of silver, 786 ounces of gold, and unknown amounts of zinc and tungsten. (Earlier miners apparently pocketed the gold, which didn't always make the official reports).

Since 1933, various lessees have driven short and unsuccessful headings from the 200, 400, and 550 levels. From May 1935 to Sept 1936, the property was leased by the "Silver-Lead Syndicate". During 1937 and 1938, the mine was again idle.

In 1940, the Cerro Gordo group was acquired by the Silver Spear Mining Corp. By this time the Cerro Gordo properties comprised 43 claims and about 550 acres. The property was operated from September 1943 - Sept 1944 by the Golden Queen Mine Company. Their work consisted of diamond drilling and drifting in an attempt to find a faulted segment of the Jefferson Ore body.

In 1944, Goldfields of South Africa reevaluated the property and the mine was temporarily reopened with little success. Diamond drilling was conducted at the south end of the mine from the 900 level in search of deep inferred fault segments of the Jefferson chimney but no mineable quantities of ore were found.

World War II brought the U.S. Army to Cerro Gordo to mine for zinc, a strategic material.

In 1946, the property was leased to W. C. Riggs and associates and purchased by them in 1949. In exploring in and around the China Stope area between the 200 and 550 levels, they did several thousand feet of diamond drilling and drove several thousand feet of drifts, raizes and winzes. Some diamond drilling was also done from the 500-foot level. A small amount of ore was developed and shipped. Cerro Gordo has been idle ever since.

Click for More About the Union Mine

In 1948 a woman name Barbara got in her brand new Chevrolet still heated from a fight with her assistant director husband in Lone Pine. Barbara was a script girl for RKO movie studios, but had roots in the Owens Valley. She found herself headed up to Lee Flat, just over the saddle from the faded ghost of the Cerro Gordo Mines, on the Death Valley side of the Inyos. It was very dark and very remote, and she wasn’t sure where she was.

She waited until morning and found a ramshackle cow camp. Rough and tumble Wally Willson opened the door when she knocked, and they fell in love immediately. Barbara divorced her Hollywood husband and moved into the cow camp with Wally. In 1949, he was approached by the last owners of the mining camp of Cerro Goro. Wally and Barbara found themselves caretakers, then owners, when W. C. Riggs had to declare bankruptcy. Wally eventually died, Barabra married Fred Coman, then when he died 8 years later, Barbara married Jack Smith.

They were awarded ownership when the prior owner, W.C. Riggs, went bankrupt while owing them back wages. In 1985 the couple transferred ownership to Smith's niece Jody Stewart, who with eventual husband Mike Patterson moved to the property and began restoring buildings for tourist and overnight use — including the American Hotel, the 1868 Belshaw House (now a bed-and-"make your own" breakfast), the general store (now a museum) and a 1904 bunkhouse (which accommodates 12 guests).

Mike Patterson and Jodi Stewart-Patterson

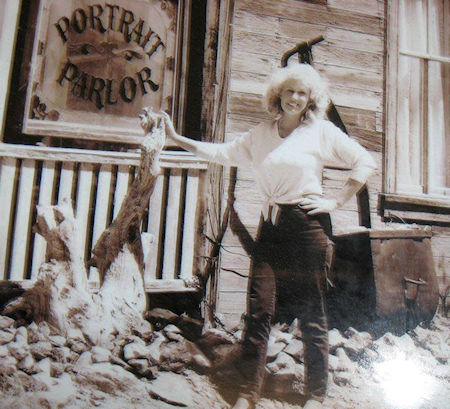

Jody Stewart-Patterson (Friends of Cerro Gordo Collection)

Jody died in 2001, Mike in 2009. A resident caretaker was kept on hand to help restore more buildings, give tours and prevent mischief. The property was inherited by Mike's son Sean Patterson, a construction contractor in Bakersfield. Two organizations were formed to take on maintainance and protection of the property - Friends of Cerro Gordo in 2012 and Cerro Gordo Historical Foundation created by Sean Patterson in 2013 (no-longer in existence).

Cerro Gordo is privately owned and currently a ghost town and tourist attraction. It still has several buildings, including the general store and the American Hotel. Permission to visit must be obtained.

The town was put up for sale in June 2018 and immediately purchased by entrepreneurs Brent Underwood and partner Jon Bier with additional investment from a small group of investors, who plan to keep it open to the public. The sellers agreed to terms with Underwood and Bier despite at least one higher bid being offered, because their vision for the future of the town, including its preservation, aligned with the sellers' wishes to continue this piece of American history.

The sale of the abandoned mining town fittingly closed on Friday the 13th of July 2018. The 24,000-square-feet of buildings and more than 300 acres of patented mining claims once averaged a "murder a week" in its hey day, and was once the largest producer of silver and lead in California.

Click for Details on the Future of Cerro Gordo Mining Town

Here are some websites with a lot of information and pictures about Cerro Gordo: