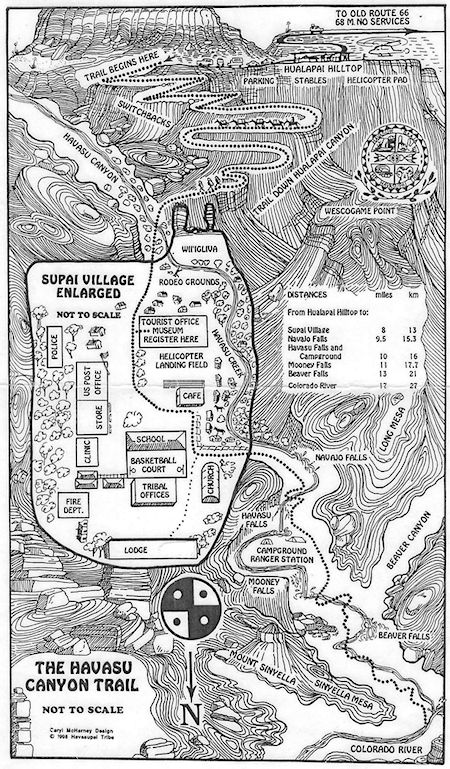

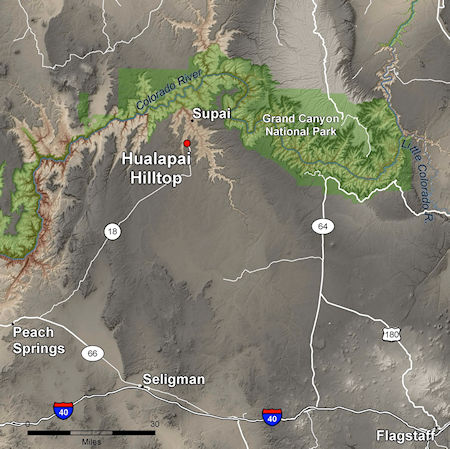

Over New Year's weekend December 28, 1962-January 1, 1963 I backpacked with Explorer Post 360 on a 23 mile round trip into Havasu Canyon on the Havasupai Indian Reservation next to Grand Canyon National Park to see the spectacular Mooney Fall.

Our group included myself, Bob Brooks, Mike O'Haver, Bill Ravenscroft, John Hoffman, Mike Fletcher, Skip Anderson, Allen Sanford, Greg O'Leary, Noel Parr, Art Ravenscroft, Kenny Dodd, Norman Hewitt, Bob Johnson, Dick Terry, Jack Weaver, Mike Harris.

The group, reddy to head down the trail into Havasu Canyon - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

We drove from San Diego to Needles Friday night and to the trailhead at Hualapai Hilltop Saturday.

The Havasupai Tribe Website has current information.

This website has excellent information and pictures. Details about the Havasupai Reservation on this Wikipedia page and the Havasupai people on this Wikipedia page.

More information on the American Southwest website, and their Hiking to Supai and Havasu Canyon page.

Check out this Guide to Mooney Falls by Nick The Rambling Man Feb 14, 2020 for good information.

The Trail Begins at Hualapai Hilltop. Hiking from Hualapai Hilltop to Supai and Mooney Falls requires a permit from the Havasupai Tribe. No day hiking is allowed. All permits are for four days-three nights. Advance reservations are required. Full information at the Havasupai Reservations website.

Supai Village is located within Havasu Canyon, a large tributary on the south side of the Colorado River. Supai Village is not accessible by road. The Havasupai Tribe administers the land, which lies outside the boundary and jurisdiction of Grand Canyon National Park. It is the only place in the United States where mail is still carried out by mules.

The campground along Havasu Creek is 10 miles from the trailhead at Hualapai Hilltop (2 miles below Supai). It serves up to 350 people. Available in campground, drinking water, restrooms, and picnic tables.

Havasupai means people of the blue-green waters. The spectacular waterfalls and isolated community within the Havasupai Indian Reservation attract thousands of visitors each year. The Havasupai are intimately connected to the water and the land. When you enter their land, be respectful, you are entering their home.

Trail Distances (one way): Hualapai Hilltop to Supai 8 miles; Supai to Campground 2 miles; Campground to Mooney falls 0.5 miles; Mooney Falls to Colorado River 8 miles.

Meet the guardians of the Grand Canyon, the Native American Indian Havasupai tribe. Matthew Putesoy, Native American chief of the Havasupai tribe, shows us the Havasupai Indian reservation in Havasu Canyon, Supai Arizona - the sacred spring waters of the Havasu Creek and turquoise Havasu Falls and Mooney Falls.

The Havasupai people (Havasupai: Havsuw' Baaja) are an American Indian tribe who have lived in the Grand Canyon for at least the past 800 years. Havasu means "blue-green water" and pai "people".

Located primarily in an area known as Havasu Canyon, this Yuman-speaking population once laid claim to an area the size of Delaware (1.6 million acres). In 1882, however, the tribe was forced by the federal government to abandon all but 518 acres of its land.

A silver rush and the Santa Fe Railroad in effect destroyed the fertile land. Furthermore, the inception of the Grand Canyon as a national park in 1919 pushed the Havasupai to the brink, as their land was consistently being used by the National Park Service.

Throughout the 20th century, the tribe used the US judicial system to fight for the restoration of the land. In 1975, the tribe succeeded in regaining approximately 185,000 acres of their ancestral land with the passage of the Grand Canyon National Park Enlargement Act.

As a means of survival, the tribe has turned to tourism, attracting thousands of people annually to its streams and waterfalls at the Havasupai Indian Reservation.

On December 29, 1962, we were on the trail at 1 and 2 p.m. and arrived at the campground at 5:45-6:00 p.m. after a stop in the village of Supai to get a permit to pass through the reservation paying fifty cents per person visior fee plus one dollar camera fee.

Hualpai Canyon to Havasu Canyon

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Looking back to cars from Hualpai Canyon

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Scene in Hualpai Canyon

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Hualpai Canyon - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Hualpai Canyon - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Hualpai Canyon - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

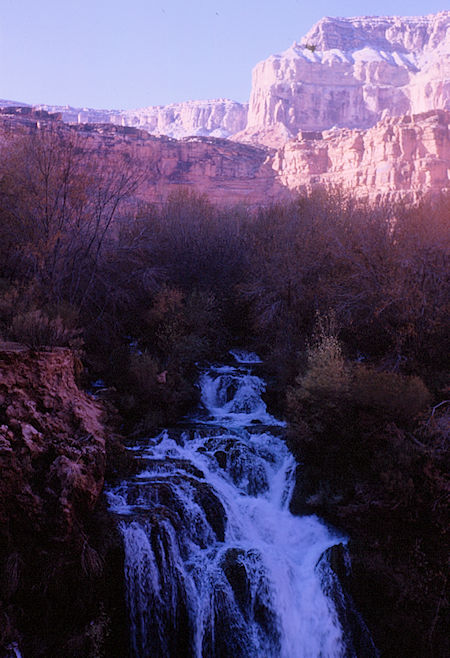

We soon arrived at Havasu Falls located 1 1/2 miles from Supai. It is the more famous and most visited of the various falls along Havasu Creek. It consists of one main chute that drops over a 90-to-100-foot vertical cliff into a series of plunge pools.

High calcium carbonate concentration in the water creates the vivid blue-green color and forms the natural travertine dams that occur in various places near the falls.

Due to the effects of flash floods, the appearance of Havasu Falls and its plunge pools has changed many times. Prior to the flood of 1910, water flowed in a near continuous sheet, and was known as Bridal Veil Falls.

The notch through which water flows first appeared in 1910, and has changed several times since. Water currently flows as one stream. In the past, there were sometimes multiple streams, or a continuous flow over the edge.

In 1962 Havasu Falls was at the border between the Havasupai Indian Reservation and Grand Canyon National Park and the campground, where we made camp below the falls, was in Grand Canyon National Park. In 1975 all of the area was added to the Havasupai Indian Reservation.

Havasu Falls - Havasupai Indian Reservation

Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

Havasu Falls - Havasupai Indian Reservation

Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

Havasu Falls - Havasupai Indian Reservation

Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

Havasu Falls - Havasupai Indian Reservation

Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

Camp below Havasu Falls - Grand Canyon National Park

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Havasu Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Breakfast below Havasu Falls - Grand Canyon National Park

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Water well at camp - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Havasu Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Havasu Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Havasu Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Campfire below Havasu Falls - Grand Canyon National Park

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Mist from Havasu Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

On Sunday we hiked down Havasu Canyon to see Mooney Falls, hiked down Havasu Creek to the Colorado River and checked out nearby old mines.

Havasu Canyon below camp - Grand Canyon National Park

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Havasu Canyon below Havasu Falls - Grand Canyon National Park

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Havasu Creek - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Havasu Creek - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Havasu Canyon - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Havasu Canyon above Mooney Falls - Grand Canyon National Pk

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Havasu Canyon - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Above Mooney Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Mooney Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

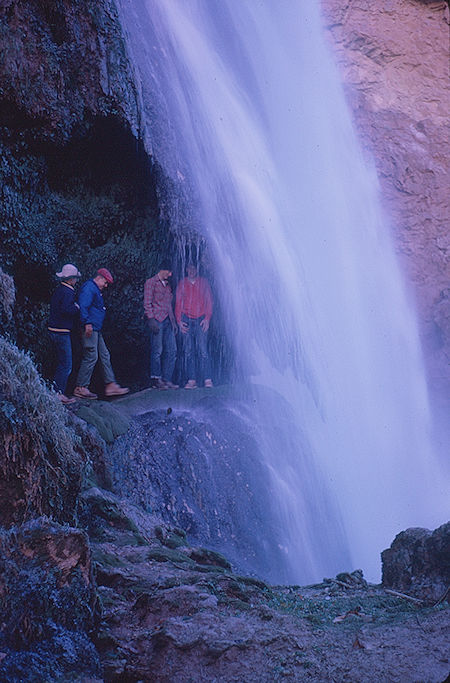

Below Mooney Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

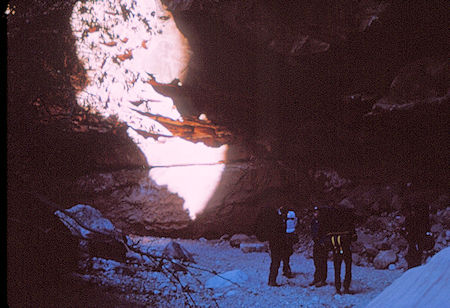

Tunnel on trail down to bottom of Mooney Falls

Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Mooney Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

The Tunnels In Mooney Falls, Havasu Canyon

by Tom Chester 14 October 1999 - Comments and feedback: Tom Chester

There is some disagreement about the origin of the tunnels in Mooney Falls. The few guidebooks which mention them repeat the same basic story. Examples:

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, miners searched for minerals throughout the Havasupai area. Most of the major activity took place in Carbonate Canyon near Havasu Falls, but tunnels and other evidence of mining activity can be found all along Havasu Creek from Havasu Falls to the Colorado River. Miners were also responsible for cutting the route through the travertine formation at Mooney Falls.

from Hiking the Grand Canyon And Havasupai, Larry A. Morris, AZTek corporation, Tucson, AZ, 1981, p. 130.

The falls take their name from a prospector who died here in 1882. Assistants were lowering him down the cliffs next to the falls when the rope jammed. After hanging helpless for 3 days, Mooney fell to his death on the rocks below when the rope broke. A rough trail descends beside the falls along the same route hacked through the travertine by miners a year after Mooney's death. You'll pass through 2 tunnels and then ease down with the aid of chains and iron stakes.

from Arizona Handbook, Bill Weir, Moon Publications, Chico, California, 1986, p. 66.

barefoot@well.com wrote me with this well-researched note debunking this story:

The stories of Mooney's death as told in Morris and other guide books all seem to stem from the account in G.W. James book In and About the Grand Canyon. Since then the story has been repeated by many authors including J. Donald Hughes and Stephen Hirst. The story runs basically as you quoted from Morris with the additions that the miners built a ladder to reach the body, which was found to be heavily encrusted with lime, then buried Mooney on the island below the falls.

There appear to be several errors in the story as told in the literature of the Grand Canyon. In the August 1959 issue of Arizona Highways there appears an article titled Mooney Falls by Helen Humphreys Seargeant that rips James story to shreds. Her father and uncle were early miners in Supai and her uncle, Alphonso Humphreys, was part of Mooney's party.

Even the name James Mooney appears to be incorrect, a copy of the Cataract Canyon Mining Claims from the Department of Mineral Resources in Phoenix dated 1879 lists the following miners: Alphonso Humphreys, D. W. (not James) Mooney, H.J. Young, W.C. Beckman, Mat Humphreys and W.W. Jones. The claim runs thru 1883, the year following Mooney's death.

A. Humphreys, Young, Beckman and Mooney had made several trips to the canyon prior to Mooney's last trip but had been unable to find a route to get below the falls. On the trip in 1882, the original party added three men, Fowler, Potts and E.L. Doheny (later of California oil fame).

In a letter in H.H. Seargeant's possession, Alphonso Humpreys wrote:

I well remember the trip that Mooney fell. We had been down in the canyon about three days when Mooney fell and was killed, and we had no way to get down to bury his remains till eleven months and a day.

The day Mooney fell we were all down in the canyon except Beckman, and when we returned to camp there was no levity amoung us. Beckman noticed that, and not seeing Mooney he asked about him, and Doheny told him he fell and was killed. The next morning before any of us was up he went down to the cliff to see if Mooney had moved. He untied the rope and tossed it down with his boots and said, this is all the funeral I can give you this time. Mooney, before starting down on his rope had pulled off his boots and asked me to lend him my belt which was a wide one. I have never seen the belt to this day, but Mooney's boots showed us the way to go down and bury him. We noticed the boots on an Indian. We asked him how he got the boots. To make a long story short, Young went with the Indian, who showed him the way he went down - a dangerous trip along a crevice in the wall of the canyon part of the way. Young wouldn't try that trail, but the Indian showed us some little caves, and we made the tunnel thru the cliff.

The next year the miners returned along with Mat Humphreys and found the Indian again who showed them a small cave leading into the overhang along the south bank. They made the cave larger and blasted out a slanting tunnel, made the steps, and suspending one of the party on a rope, set the iron spikes in the cliff below the tunnel. Mat Humphreys did the drilling and said that he almost stood on his head while doing so.

It is interesting to note that there is no mention of Mooney hanging from the rope for three days, a twist to the story apparently invented by James. The miners buried Mooney's preserved, lime-encrusted body on the little island below the falls, but one of the elder members of the tribe told me that a flood had exposed the remains and Mooney was reburied up on a ledge on the west side of the canyon. The exact location is currently unknown.

The ladder below the falls was built later leading to a mine entrance. Originally the lower part was of wood and it became something of a feat for the young men of Supai to climb the ladder and jump into the creek. In 1954 a rung broke on the wooden portion of the ladder causing severe injuries to a youngster. To prevent a similar accident in the future the Indian Agent at the time had the lower section of the ladder removed, but the metal upper reaches of the ladder can still be seen today.

On the other hand, Bob McNichols writes me that:

The tunnels you went through to get from the top of Mooney to the bottom are natural, not blasted. They are created from the water dripping off the top and the travertine dissipating from it, leaving the open space behind it.

from email of 10 October 1998.

I questioned Bob about his interpretation, since this formation process is contrary to the explanation given in the book Grand Canyon Geology (eds. Stanley S. Beus and Michael Morales, Oxford University Press, 1990), which states on pp. 479-480:

The travertine is formed by the precipitation of calcium carbonate as the creek waters warm and evaporate. The travertine tends to encrust the surface and to take the form of any objects over which the water passes.

Hence the usual process is for the travertine to "increase its width and size" (p. 480), which would fill in holes rather than enlarge holes or create new ones. The process that Bob espouses is what happens in cave formation, where water that is not already saturated with calcium carbonate dissolves limestone.

However, Bob McNichol's credentials are impressive and he has a lot of experience observing the travertine in Havasu Canyon. He writes:

I've worked with the Havasupai for over 20 years and have spent a lot of time watching the travertine form, break away, and reform. I have spent a lot of time with my staff blasting out natural travertine dams which cause the water to back up too deep for the horses to cross the trail, and rebuilding the Havasupai Falls dam after the travertine pools washed out and drained the pool below Havasupai Falls where everyone swims. I have worked with Wright Water Engineers who worked on rechanneling the creek, building bridges, etc. after the floods. I've worked with USGS from Flagstaff and Denver on water assessments, quality and quantity. I've worked with Indian Health Service on water supply and distribution; with BOR on irrigation operation and maintenance; with EPA and Corps of Engineers on Section 104 and 106 Clean Water Permits, with NRCS on feasibility of aquaculture; with ASCS and SCS on farmland planning; UofA and Mohave County and Coconino County Extension on lots of water issues; and numerous others.

When they have a flood or other emergency, I am the first one they call. I work with the tribal attorneys on water rights protection. I assist them with the Forest Canyon Village development responses which was first proposed to pump water from the aquifer which feeds Cateract Creek. I've assisted in funding and contracting a number of wells, the most recent on Bar 4, 3200 feet deep. I know Havasupai.

Travertine at Mooney Falls - Grand Canyon National Park

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)If you look at your photos of Mooney Falls (or Havasu Falls), you will see the veils of travertine that form leaving large empty spaces behind them. Many of these veils have broken off during the floods over the years but still very apparent how they form. If you watch as you are climbing through the tunnel, you can easily observe the natural formation with the rough natural surface, the pieces of wood which have travertined over and the way wood and other materials are laid thru the travertine in a natural setting.

The veils occassionally break off from their own weight, or through flooding which leaves an obvious change in the way the precipitate builds up. If you have ever swam over behind Havasu Falls and climbed up on the ledge directly behind the falls, approximately 12 feet above the water level, where we go to dive into the Falls, that also is very obviously created from the travertine veil. The tribe has done a little work on the trail at Mooney by chiseling in some steps and footholds, installing the chains to hold on to, and making the trail more passable, but the tunnels are natural.

The mines never amounted to much. There was some lead hauled out but it never became economic. The shafts you mention were primarily from the prospecting.

Steve from Prescott, AZ contributed some key observations on this issue:

I am an experienced Supai hiker with 15 years of annual trips and observations. Those tunnels ARE man made, even though there were probably natural openings where they were built. They have square corners inside and steps on the floor. No natural process here.

Perhaps the truth here is a bit of both stories, as is often the case in contested matters. The Arizona Highways article states that the tunnels began with a natural cave, which was enlarged by blasting, with man-made tunnels created in addition to the natural cave. Hence the current-day tunnels would show both evidence of being made by man in places and of being natural in others.

I thank the three contributors quoted above for enlightening me and readers on this fascinating story. If any readers have additional historical or geological information that would shed further light, please email me.

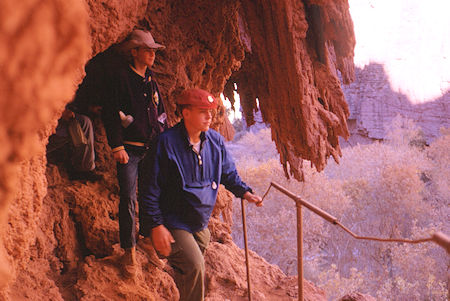

Trail down to bottom of Mooney Falls

Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Trail down to bottom of Mooney Falls

Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

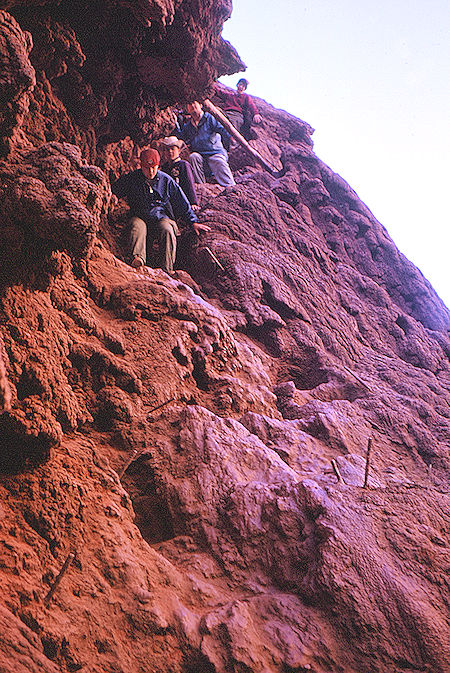

Trail down to bottom of Mooney Falls

Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Since then, as shown in the video, the "trail" has been improved by the Havasupai Tribe with the addition of chains to hang on to while descending and wood ladders near the bottom.

Descent of Mooney Falls 2014

Mooney Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Mooney Falls - Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Read about the early mining operations near Mooney Falls. NOTE: The reference to "Bridal Veil Falls" in this article refers to the renamed "Havasu Falls". "Cataract Canyon" refers to the renamed "Havasu Canyon".

OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT

GRAND CANYON NATIONAL PARK

From PROSPECTING IN GRAND CANYON (Circa 1925)

The Cataract Canyon Claims

Pb, Zn, Ag, and V.

Cataract Canyon, as far as we know, was first prospected for minerals about 1885. It was then in a region 55 miles from the nearest railroad. The intervening country is itself difficult enough, and there were no trails, springs, waterholes or streams. All of these difficulties were overcome, and they were such that they can hardly be appreciated even by a present day visitor, and not at all by those who have not seen this region of vertical cliffs, deep canyons, and towering rock masses of forbidding table lands.

It is said the first prospectors let themselves down the Canyon with ropes. This can well be believed and it is a certain fact that when the Canyon floor below Bridal Veil Falls was reached, pack animals had to be lowered over the cliffs of Mooney Falls by means of ropes and a derrick.

Mooney Falls gains Its name from the fact that Mooney, who was an ex-sailor, attempted the first descent of the cliff by means of a rope lowered from the top. He paid for the attempt with his life, the spinning rope causing him to lose his hold when but a few feet over the cliff and fall to the rocks below. Of how his companions finally reached and buried Mooney's body, need not be told.

Eventually the cliff was conquered by inclined tunnels under the travertine deposits, supplemented by steps cut in the rock and pieces of steel set alongside such steps for hand holds. These steps and hand irons are still used. Indeed hours could be spent in reciting the great obstacles the early prospectors had to overcome in their efforts to uncover the mineral deposits of the region.

From 1885 to approximately 1901, mining was principally for the Pb-Ag ores, and about 100 tons of high grade ore was shipped to smelters during that period, but the inaccessibility of the region and the long packing and hauling costs made this mining a failure.

About 1902, an eastern company was formed for the purpose of prospecting the lower part of Cataract Canyon. It was known as the Grand Canyon Gold & Platinum Co. Platinum was supposed to have been found near the River. This company tried to build a road down into the Canyon from Hilltop - part of it is now used as a trail by the Supais. This company spent about $75,000 in attempting to build this road.

About 1906, a man named W. I. Johnson came into the district and staked a number of claims and located various water rights on Havasupai Creek. He erected a small concentrator plant and ran several hundred tons of lead ore through it. Some of these concentrates still on the ground are estimated to contain 60% Pb with perhaps 20 oz. Ag per ton.

Johnson was not aware that these lead ores also contained vanadium and so made no attempt to recover this valuable metal. Johnson was unable to make a commercial success of the proposition, but continued to hold the claims by assessment work. In 1919, he interested a mining engineer of Prescott named Heberlein in his claims, and in 1921, Heberlein took an option on the Johnson claims. Since that time approximately $15,000 has been expended in actual development work.

The occurrence of the ores in Cataract Canyon has never been thoroughly studied. They occur in solution cavities in the limestone and the first thing formed was great crystals of calcite--these later caved in and formed a breccia, then solutions carrying lead and silver permeated the breccia and replaced the limestone with galena. Vanadlum-bearing solutions came later.

No igneous rocks appear to be connected with the deposit though thorough search has never been made.

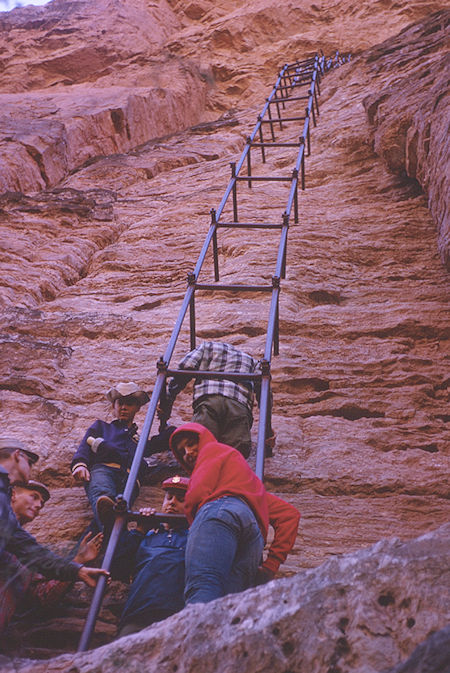

Ladders below Mooney Falls leading to the Old Mine on the West Wall

Old ladder supports from below Mooney Falls to mines

Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Ladder support structure (left) to mines (top)

from below Mooney Falls

Grand Canyon National Park - Dec 1962

(part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Mining Ladders 1905

by Maude and Bartoo

Ladder framwork 1961

NPS by J. Bailey

Mining interests were present in the canyon in the late 1800's-early 1900's. Tunnels are a familiar sight in the campground area with the deepest of them around 300 feet.

The largest of the mines is in Carbonate Canyon, adjacent to Havasu Falls, where rails and timbers still can be found descending three levels.

Lead was mined here for the last time during WWII by the Havasu Lead and Zinc Company. Their hard rock mining camp was where the campground now resides.

Below Mooney Falls, the famous pipe "ladder" ascended to a vanadium deposit.

Remains of mining operations - Grand Canyon National Park

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Mine opening on canyon wall - Grand Canyon National Park

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

Mooney Falls and Havasu Creek - Grand Canyon National Park

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975)

On the trail out of Havasu Canyon - Grand Canyon National Park

Dec 1962 (part of Havasupai Indian Reservation as of 1975

On the trail out to Supai Village

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

We hiked out through Supai on Monday 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. and drove to Kingman for the night.

On the trail out to Supai Village

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Looking south below Supai Village

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

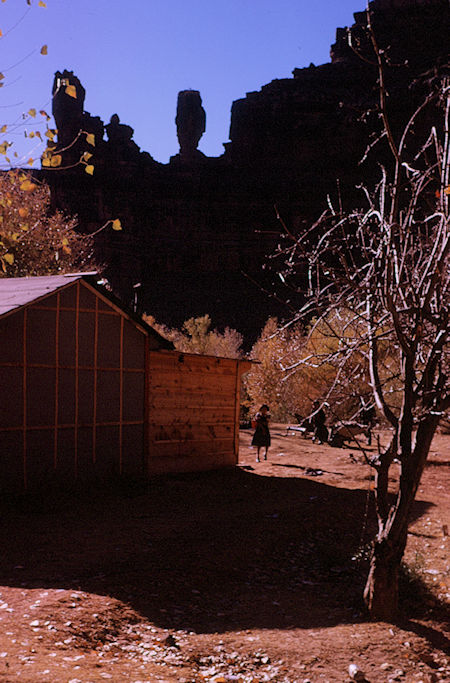

Supai Village - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

The Guardians from Supai Village

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

The Guardians over Supai Village

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Supai Village - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Supai Village - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

The Guardians over Supai Village

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

The Guardians over Supai Village

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Two prominent rock spires on the west side, known as Wigleeva, are believed by the Havasupai to be guardian spirits which watch over the tribal homeland, and will ensure continued prosperity as long as they stand.

Supai Village - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Supai Village - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

The Guardians over Supai Village

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

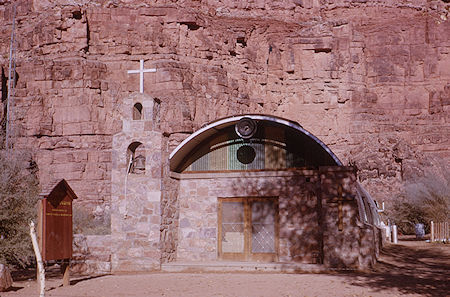

Church at Supai Village

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Supai Village school - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Supai Village - Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Steam Hut in Supai Village

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Hualpai Canyon on the way out

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

Hualpai Canyon on the way out

Havasupai Indian Reservation - Dec 1962

We headed home on Tuesday, arriving at 3 p.m. Beautiful weather - cold and clear except late Monday and Tuesday overcast. Sun hard to find at campground in winter season due to high canyon walls. This is a very scenic area and well worth the trip.

Here are a couple of videos. The long one on the right covers the entire trail. Both show the great scenery and waterfalls.